Cymatics

The question of the origin and social function of art has always informed the evolution of creative practice. The advent of Chat GPT and AI-generated art has revived an investigation into the nature and value of creative work, rendering a precarity to the once privileged notion of the individual artist as creative genius. The history and development of artistic innovation can be characterized by a constant evolution in form and concept, and the ways in which historical and cultural contingencies prompt the development of new artistic works that arise through a remix of materials and revolution in technique. The post-impressionists, for example, retained the basic techniques of their impressionist predecessors, while deviating in subject matter and emotional tone in response to social and political conditions. This process of artistic development – once a lengthy process of remix and revolution – can now be instantaneously mechanized by feeding “write a poem on technology in the style of Jane Austen” into a function.

The ways in which new forms of technology have so quickly upended our understanding of the creative product, thus implicates our post-Enlightenment obsession with individualism and originality, and calls for a reframing of the relationship between subject and aesthetic object. The study of cymatics, particularly through the analysis of the relationship between observer and the object (form of sound) perhaps offers an alternative mode of inquiry that may recontextualize our past fixation with human creativity, thus reframing our understanding of the nature, value, and purpose of art.

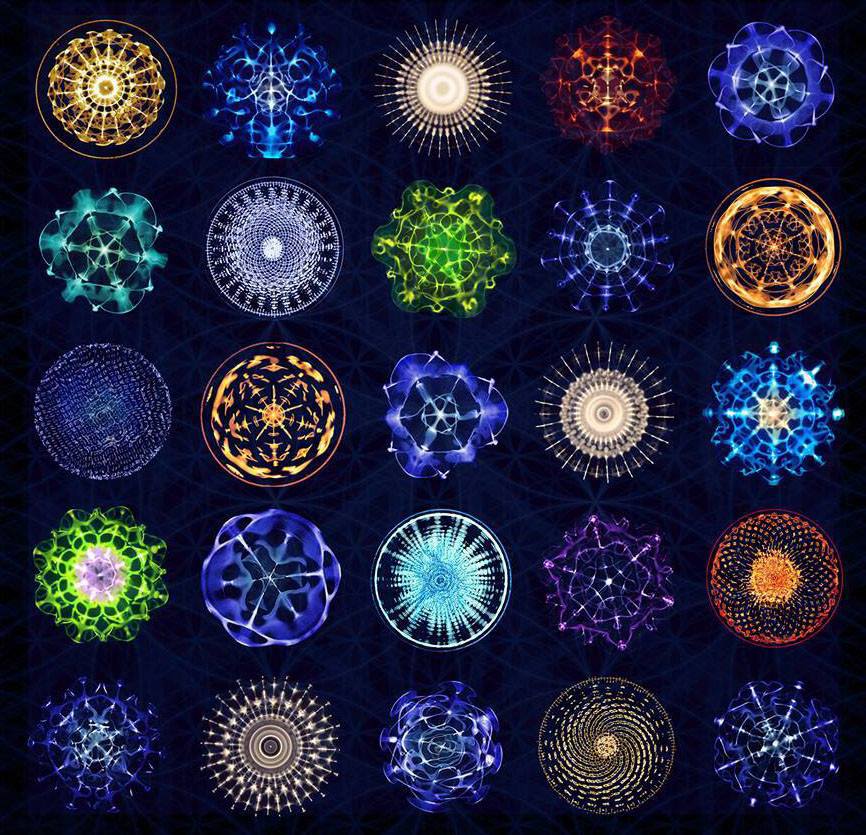

The basic physics of cymatics operate in the following way: upon exciting an object at a certain external frequency (by playing sound from an external source or mining an object’s natural frequency) vibrations displace air molecules and produce a sound wave with a particular frequency and amplitude. In the arc of such a sound wave, air molecules become hyper-compressed at certain points, reaching a state of equilibrium and temporary stillness. These specific points of the wave are known as nodes, and serve as the locus and outline for the subsequent artistic visualization. An object’s natural frequency corresponds to its rate of vibration when disturbed by an external source. Through Svaram’s experimentations with Chladni plates, one can visualize the underlying sound wave by placing sand on these metal plates – which, when disturbed at its natural frequency, produce mesmerizing patterns. These uncanny (yet also somewhat familiar) designs arise through the accumulation of sound around these nodes. The fluctuating motion of uncompressed air molecules results in the movement of sound towards the outlines produced by the nodes. As one manipulates the Hz frequency of the external source – the wave wraps around the object an integer number of times, resulting in the transition between these mesmerizing patterns. With cymatics, therefore, one mines the vibrational potential of the unseen world– unifying our propensity for aesthetic fulfillment with the fundamental frequencies of reality.

Much of the interpretation of these aesthetically pleasing designs – which, by nature of its somewhat pop science feel and TikTok friendly visuals – involves its correspondence with naturally-occurring patterns. After all, cymatic images have much in common with the geometry of tortoise shells, flowers, and snowflakes, lending credence to the belief that a universal energy – mediated through sound and vibration – permeates and produces form. Some have even posited the use of cymatic images as a model for conceptualizing mood and consciousness, noting that the fluctuations in cymatic visuals based on different Hz inputs may correspond to the effect of sound on the vibrational frequencies of various parts of the brain – a weighted sum of which, could form consonant or dissonant harmonic rations that subsequently correspond with states of consciousness.

Harsh Gandhi, a cymatics researcher at Svaram, is not only interested in juxtaposing cymatics with naturally occurring patterns in order to create unified theory of form, but also seeks to investigate the ways in which seemingly inanimate objects such as water or light may exhibit properties of consciousness. Experiments show that the molecular shapes of crystals vary in reaction to musical genres and the setting of different intentions. It seems that– depending on whether someone plays Bach or Beethoven, or sets negative or positive emotions, water will inhabit a unique form.

I find it intriguing that an analysis of the effect of sound on a particular medium – whether a Chladni plate or water – could ostensibly be found in a philosophical treatise on media theory; a fundamental aspect of the sound wave’s motion is that it does not change the medium through which it passes, it only manipulates the energy. In contrast, artistic innovation frequently involves the overlaying of forms over (and between) new mediums and contexts, necessitating a fundamental transformation of the medium. In contrast, the visual manifestations of sound, evinced by cymatics, are self-contained; vortices of geometric patterns are instantiated as a mere side effect of the unseen vibrational frequencies of matter. While the wave’s amplitude and frequency may change, matter remains in its original form, yet is rendered in a medium cognizable to the human mind. In this way, the visual art produced by cymatics might be understood as the purest, most unadulterated form of art- which has succeeded in connecting one’s inner mental infrastructure with the vibrational frequencies of the unseen outer world.

The transformational potential of the field of cymatics, therefore, may lie in this potential of geometric manifestation of sound to act as a gateway between human consciousness and the noumenal world. 18th century philosopher Kant, in the Critique of Pure Reason, famously argued that – while we could never fully comprehend the world as it actually is – we’re able to make sense of reality due to the way in which the appearance of the world corresponds to the inner structure of our mind. Kant stipulated that space, time, and causality are certain shared features of the inner and outer worlds, allowing for a legitimate understanding of reality; in light of research into the physics of sound, we might add vibrational frequencies to this list. While Kant argued that we can’t access the actual reality of objects (we only interact with them to the extent that they are perceivable by our minds), we can use his argument to analyze our relationship to the form of sound. Ascribing to Kant’s view that appearance acts an intermediary because of certain features that are shared between the observer and the observed, we might conclude that the work of cymatics bridges that gap between mind and matter. The fact that the vibrational frequencies of sound are rendered cognizable through their interaction with the vibrations of the neurons in our own visual cortex, illuminates the ways in which reality arises from interrelated networks of oscillation.

It is this intricate, reciprocal relationship between the vibrational frequencies of the inner and outer worlds which is made explicit in the work of cymatics. The potential of human beings to create form (which has historically been propelled by a fixation with individuality, and has been called into question by AI) can be reframed to focus instead on the ways in which form connects the individual with unseen worlds. If it were proved definitively, for example, that water exhibits consciousness, we might understand the work of cymatics as an artistic form that acts as a medium for conversation, thereby revolutionizing our traditional notion of art as understood through the language of property rights and individualism.

In our never-ending inquiry into human consciousness, therefore, we may move away from the idea that creative production represents the utmost essence of an individual, and instead investigate the ways that form both arises from and interacts with the vibrational frequencies of the universe, resulting in the intricate, pulsating feedback loop that undergirds reality. This modality of conceptualizing the artistic process would shift away from the rather egotistical, 21st century lens of artistic creation as a means for human domination and ownership– and instead re-engage our minds in the creative, dynamic, reciprocal process of deep listening to those subtleties of sound.

— Sahana Narayanan